(Photograph: Courtesy Eden Hills Country Fire Service)

Smoke taint. It’s a pretty commonly discussed topic throughout the Hills in the last month or so.

I’ve been chatting about it at the cellar bar and with friends and heard a few different versions of the story.

From…

“the grapes will be fine because it was too early for them to be affected”

to…

“if smoke has been present around vines then the grapes will be useless”

The truth is… we honestly don’t know. They could be fine, they could be useless or perhaps somewhere in between?

I know I’ve covered this before, but let’s just have another quick look at the science behind smoke taint and what’s happening in the Adelaide Hills to assist growers to assess the damage.

What is ‘smoke taint’?

As the name suggests, smoke taint is an undesirable characteristic in wine when the grapes are exposed to smoke.

And although we talk about those typical smokey characteristics of a wine which is aged in toasted oak barrels… it’s definitely not that. Common descriptors for smoke-tainted wines include burnt, medicinal and campfire. The best quote I read during my research on this topic came from a guy in California who said… “if you’re particularly fond of licking wet ashtrays, you’ll like this wine.”

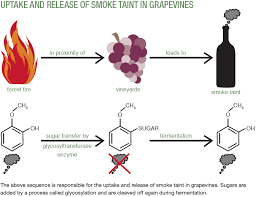

Unfortunately, smoke taint isn’t caused by just a residue on the grape. You can’t wash it off. When wood burns, it releases aroma compounds called volatile phenols. In the vineyard, these compounds can permeate the grape skins and attach themselves to the sugars inside to form molecules called glycosides.

Unfortunately, smoke taint isn’t caused by just a residue on the grape. You can’t wash it off. When wood burns, it releases aroma compounds called volatile phenols. In the vineyard, these compounds can permeate the grape skins and attach themselves to the sugars inside to form molecules called glycosides.

This process renders the phenols no longer volatile, meaning their smokiness cannot be detected by smell or taste. However, once the grapes are fermented, the acidity in the resulting wine will begin to break the bonds between the sugars and the phenols, rendering them volatile once again (and hence detectable).

This typically happens during fermentation but can continue to occur after the wine has been bottled. It can even happen right as you take a sip: The enzymes in your mouth are able to break down any glycosides that remain, and the undesirable aromas can be vaporised as you taste. A wine might smell fine but taste off.

Factors which affect the uptake of smoke taint

According to the AWRI, the risk of smoke exposure causing a perceptible taint in wine is determined by a number of factors, including…

- stage of grapevine growth and development,

- the grapevine variety exposed,

- smoke composition,

- duration of exposure

Stage

Stage

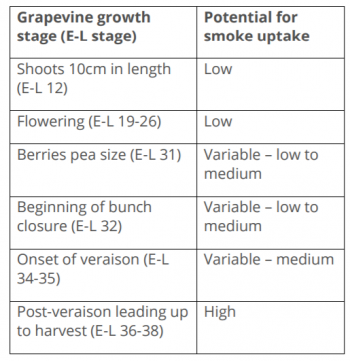

Research has shown that the period between veraison and harvest is when grapes are most susceptible. If you have a look at the table on the right you’ll see the potential for smoke uptake for all the different stages. This is where we see the first bit of good news for vineyards exposed to smoke in the December 20 fires. At that time, vines in the fire-affected areas were only around E-L 31 (or less).

Variety

It has become apparent that certain varieties seem more susceptible to smoke taint. But the jury is still out on exactly which ones and why. More research is being done in this area. But for now, it is believed that thicker-skinned varieties are better off. So, Sangiovese is more sensitive than Cabernet Sauvignon.

Interestingly, you won’t see smoke taint in white wines nearly as much as you would in reds. The compounds are concentrated in the skins, and whites don’t typically sit on their skins during fermentation as reds do.

Composition

The exact amount of smoke exposure which results in a perceptible taint in wine is not well known. This is because the chemical composition of smoke changes rapidly in the atmosphere. It becomes lower in the concentrations of volatile phenols over time. This means that smoke from recently burnt woody materials will contain higher concentrations of free volatile phenols, and will have greater potential to cause smoke taint in grapes and wine.

Duration

A 2008 study, conducted in part by Western Australia’s Department of Agriculture and Food (DAFWA), found that even 30 minutes of heavy smoke exposure to grapes could cause smoke taint in subsequent wines. So “not long” is the answer to that one!

Detection

Research into methods for detecting smoke taint is ongoing.

Currently, winemakers can send samples of grapes and juice to research institutions or private companies, where they will be tested for two volatile phenols. These are the most common markers of smoke taint. Low levels of these compounds naturally exist in wines. Oak-aged, non-tainted wines can have even more.

Though we know high levels of these compounds will indicate smoke taint, there is no threshold level that will definitely signal that. It depends on how much volatile phenol is released during the winemaking process. And to figure that out you have to… well, make the wine. Not the greatest use of your time and money if you’re going to end up with a smoke tainted wine.

The story in the Adelaide Hills right now is that growers are encouraged to turn a small parcel of potentially affected fruit into wine for testing.

As many people affected do not have the facilities or resources to undertake the small-lot winemaking, a contract winemaking facility in Lenswood has offered to help with the preparation of samples ready for testing by the AWRI.

PIRSA has also just announced that funding will be available to subsidise laboratory testing for individual wine grape growers affected by both the Adelaide Hills and Kangaroo Island bushfires.

What Can Winemakers Do?

Even if vineyards and grapes are exposed to smoke, it’s not the end of the world for their wines. The AWRI has come up with around a dozen practical tactics for managing smoke-exposed fruit. The key ones being…

- Hand harvest fruit to minimise breaking or rupturing of skins (where the volatile phenols are)

- Exclude leaf material to limit smoke-related characteristics (the leaves adsorb the phenols as well)

- Avoid maceration and skin contact during the winemaking process

- Keep fruit cool to extract less smoke-related compounds

- Whole bunch press to reduce extraction of smoke-derived compounds

In addition to these strategies, advances are happening all the time.

And, while what happened here in the Hills on December 20 is devastating… it is also providing us with invaluable data. Growers, along with the AWRI (who are experts in the field of smoke taint) will be collecting data which will be used to further research in this area.

Now, just back to the overall damage to vines in the Adelaide Hills for a second…

Is it clear exactly how much damage there was yet?

I’ve mentioned Greg Horner from Mount Bera Vineyards in a previous post. His vineyards were severely affected in the Sampson Flat bushfires of 2015. He’s been writing a blog to share his experiences and help producers affected by the Cuddlee Creek fire in their decision-making processes.

Wine Australia has put together this fabulous case study video of Greg which explains why it is still too early to predict the full extent of damage from our most recent fire…

With the high temperatures in recent times and looking into the future. I am interested in the effect heat has on stored wine. I have read about temperatures for storing wine and temperatures that should not be exceeded. My storage facilities possibly like many others are pretty basic and as a result my wine may have exceeded recommended temperatures. I have know way of knowing until I open a bottle. But even then I don’t know what I am looking for in smell or taste for that matter. Can you shed some light.

Hi Robert,

First, you should check out this post I wrote last year… http://blog.somerled.com.au/archives/range/wine/how-to-store-wine-when-its-46-degrees-outside/

It should answer some of your questions.

The key is not necessarily to stop the wine from getting too hot (although obviously that’s the best scenario), it’s more important to make sure there are not massive variations in temperature over time. So the place you select to store your wine in should be cool, but also the temperature should be as constant as possible.

You’ll definitely know if your wine has been “cooked”. The taste will be really “jammy”… like stewed fruits.

Also, if your wine has a cork in it, a telltale sign is if the cork has been pushed out a little due to the increase in pressure.

I hope that helps!

Maree