Brandy, fortified wine, sherry, madeira, marsala, vermouth, cognac… what does it all mean??!

Brandy, fortified wine, sherry, madeira, marsala, vermouth, cognac… what does it all mean??!

And are they really all made from wine?

This week I tackle a topic I have been avoiding, simply because I just don’t get it! But it is probably time I put my research hat on and get to the bottom of it. Mostly for my sake, but hopefully you’ll get something out of it too!

Just as a quick aside, I visited the Barossa last weekend. I’ve never been much of a gin fan (too much good wine to drink!), but I came across a Shiraz Gin. While still not really my thing, I was intrigued by the idea of using grapes to produce spirits…

… that was until it was quietly and subtly pointed out to me that in fact, grapes have been used to make spirits long before fancy gin makers started experimenting with them.

How embarrassing!

Right, so let’s get to the bottom of it once and for all…

Brandy

I think the only thing I have ever done with brandy is put it in my Christmas pudding.

But it turns out people like to drink it as well!

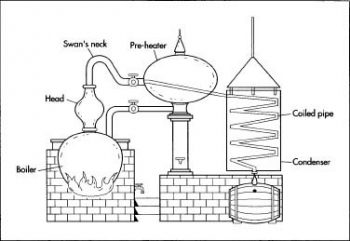

The name brandy comes from the Dutch word brandewijn, meaning “burnt wine.” Which is apt as most brandies are made by applying heat to wine. The heat drives out and concentrates the alcohol in the wine. Because alcohol has a lower boiling point (78°C) than water (100°C), it can be boiled off while the water portion of the wine remains in the still. This process is called heat distillation.

The name brandy comes from the Dutch word brandewijn, meaning “burnt wine.” Which is apt as most brandies are made by applying heat to wine. The heat drives out and concentrates the alcohol in the wine. Because alcohol has a lower boiling point (78°C) than water (100°C), it can be boiled off while the water portion of the wine remains in the still. This process is called heat distillation.

The distillation process can be repeated several times depending on the desired alcohol content.

For example, most fine brandy makers will double distill their brandy. After the first distillation, which takes about eight hours, every 3L of wine have been converted to around 1L of concentrated liquid with an alcohol content of 26-32%. The product of the second distillation has an alcohol content of around 72%. The higher the alcohol content the more neutral (tasteless) the brandy will be. The lower the alcohol content, the more of the underlying flavors will remain in the brandy, but there is a much greater chance that off flavors will also make their way into the final product.

The brandy is not yet ready to drink after the second distillation. It must first be placed in oak casks and allowed to age. Most brandy is less than six years old. However, some fine brandies are more than 50 years old. As the brandy ages, it absorbs flavors from the oak while its own structure softens, becoming less astringent. Through evaporation, brandy will lose about 1% of its alcohol per year for the first 50 years or so it is “on oak.”

Fine brandies are usually blended from many different barrels over a number of vintages. Because most brandies have not spent 50 years in the barrel, which would naturally reduce their alcohol contents to the traditional 40%, the blends are diluted with distilled water until they reach the proper alcohol content. Sugar, to simulate age in young brandies, is added along with a little caramel to obtain uniform color consistency across the entire production run.

OK, so in very basic terms, brandy is made by separating the alcohol from the water in wine to create a super-concentrated wine product which is then aged in barrels.

You still with me?

Just like wine, the location of the production of certain types of brandy dictates the name given to that brandy (just like wine coming from regions such as Champagne, Burgundy, and Bordeaux)…

Types of Brandy

Cognac

Cognac is by far the best-known brandy of all. These brandies must be produced within the Cognac region, just north of Bordeaux, and matured in oak barrels. Generally speaking, young Cognacs will have light and lively fruit and floral aromas. The influence is evident in older examples, along with mature aromas and flavours of dried fruits.

Armagnac

Armagnac is another production area in France renowned for high-quality brandies. Differences in the way these brandies are produced generally mean Armagnacs having bolder, more complex aromas and flavours compared with Cognacs. For example, in Armagnac, brandies don’t have to be matured in oak barrels, so you’ll find clear brandies from the region with no oak aromas, emphasising their fruit and floral aromas instead.

Calvados

France’s famous apple brandy, known as Calvados, is made in production regions particularly well-suited to growing apples in Normandy, northern France. Because Calvados is usually produced in very large oak vessels, oak influence is minimised and apple brandies will retain pronounced aromas of apple, even after long ageing.

Grappa

Italy is famous for grappa – a pomace brandy made with the skins of grapes that are discarded by winemakers. The pomace from black grapes includes some alcohol. This is because black grape skins give red wines their colour and need to be included in the fermentation. Therefore, black grape pomace can be distilled directly. Typically, white grape pomace does not include alcohol as it is discarded before fermentation. However, it does still contain some sugars. By adding water, the distiller can produce a sugary liquid that can be fermented and then distilled.

Italy’s grappas are rarely matured in oak, so they showcase the varietal characteristics of the grapes used to produce them, as well as pronounced herbaceous flavours from the pomace.

Pisco

One other type of brandy, produced in Chile and Peru, is called pisco. These are pot-distilled brandies made from highly aromatic grapes, especially from the Muscat family of grape varieties. Most examples of pisco are not aged in wood so as to preserve the natural aromatics of the grapes used to produce them.

Fortified wines

The word fortify means to (make like a “fort” and) “strengthen”.

So, to fortify a wine you’re basically just increasing the strength (or alcohol content).

Contrary to popular belief, this higher alcohol content is not a result of distilling these wines; it is due to the addition of spirits. Something like brandy!

So, why did winemakers add spirit to their wines?

Well, before refrigeration, wine bottles, and the ability to airmail products, winemakers had a serious problem. Wine casks were not as air-tight as wine bottles, so during long sea voyages, the wine would oxidize and turn into acetic acid (vinegar). Desperate to prevent this loss of product, winemakers added spirits to their wine, which resulted in a higher alcohol content, less spoilage and much happier customers (probably due to the higher alcohol content!!).

Types of Fortified Wine

There are many different types of fortified wine that are available, but each has its own distinct characteristic that makes it unique in its own right.

There are many different types of fortified wine that are available, but each has its own distinct characteristic that makes it unique in its own right.

Port & Sherry

The two most well-known varieties of fortified wines are port and sherry.

Both of these are fortified with brandy and, like most wines, are named for their locations of origin.

- Port comes from the Douro Valley in Portugal.

- Sherry is a Spanish wine that comes from Jerez de la Frontera.

However, there are some key differences between these two types of wine. Sherry is a dry fortified wine, which means that the brandy is added after fermentation is complete. Port, on the other hand, is a sweet wine, created by adding brandy mid-way through the fermentation process. Fortifying the wine with this method will stop the sugar from turning into alcohol because the wine yeast cannot tolerate alcohol levels above approximately 16%.

Most of the port wines you come across will be red, but there are some white and dry/semi-dry versions out there. Likewise, Sherry is also available in a few different styles. These include dry and light, to dark and sweet.

Madeira & Marsala

Other types of fortified white wines include Madeira and Marsala. Marsala wine originates in Sicily and is also fortified using brandy after fermentation, similar to the process used when making sherry. Winemakers who prefer a sweeter Marsala add a sweetening agent, rather than adding the brandy earlier.

Madeira wine also tends to be similar to sherry, but winemakers produce sweeter Madeira wine by using a Port-like process of fortification. This style originated in the Madeira islands.

Vermouth

Vermouth is probably better known as the “other” ingredient in a martini, but it’s great to sip on its own as an aperitif.

It is a fortified wine flavoured with aromatic herbs and spices (otherwise known as “aromatised”) using closely guarded recipes. Some of the herbs and spices used may include cardamom, cinnamon, marjoram and chamomile. Some vermouth is sweetened; however, unsweetened or dry, vermouth tends to be bitter.

There are others, but we could be here all day if I described them all!

And before I go, just a quick word on that Shiraz Gin I mentioned at the beginning.

Rather than using finished wine to flavour the gin, whole Shiraz grapes are steeped in gin for a couple of months. Because the grapes haven’t been fermented it adds sweetness, along with all those lovely Shiraz flavours and tannins! Definitely worth a try if you’re a gin lover.

For me though… I’m happy to stick with a Somerled Shiraz for now!