Another busy week for Rob as vintage 2022 continues.

Before I get into this week’s topic, here is a very quick update…

Pinot noir for Light Dry Red (LDR)

The fruit for this one is coming from Kim Anderson in Charleston. It was hand-picked yesterday (Wednesday 23rd).

Pinot Noir for Rosé

Paul Henschke at Summertown will hand-pick this for us tomorrow (Friday 25th).

Chardonnay

The rest of our chardonnay will be machine-picked from Kim’s vineyard on Saturday (26th).

Pinot Noir for dry red

This one should be ready to pick from Kim’s vineyard next Tuesday (29th)

So, what happens to the grapes once they are picked?

I am so glad you asked (again! I’m at risk of repeating myself here, but it’s an important topic)!

The idea is to get the fruit from the vine to the winery as quickly as possible. And when they get there, they are turned into juice.

It’s the very first step in the winemaking process.

You’d be forgiven for assuming it’s a fairly straightforward step. Give them a good squish and collect the juice… right?

Well, sort of. But it’s also a little more complicated than that.

Let’s find out more…

Crushing and de-stemming

Two separate processes, done at the same time by a fancy machine called a “crusher destemmer”… funnily enough!

Here is a video I found on YouTube to help you visualise the process (on a smaller scale obviously. They have bigger, mechanical ones in the winery)…

Crushing (or foulage in French) is generally described as “breaking open the grape berry so that the juice is more easily available to the yeast for fermentation” (thanks Jancis Robinson for letting me borrow that from The Oxford Companion to Wine, Third Edition.)

The juice which is released from this process is known as “free run” juice.

Free-run juice is super important in certain types of winemaking. Take our Sparkling Pinot Noir for example. If you collect this juice and separate it from the skins as they are being crushed, then the juice and the skins spend very little time in contact.

(Note: that’s not what they are doing in the video. In that example they are collecting the juice and crushed grapes in the same container and leaving them in contact)

Why is that important? Well, skins are where the colour and tannins are (for red varieties). So, if you want a pale wine with no tannins then you’re going to want to use the free run. Which is exactly what Rob does.

When you’re making red wine, the free run is left in contact with the skins until fermentation is complete.

Why do you need to get rid of the stems?

In most cases, stems are removed prior to fermentation because they are full of tannin. The skins and seeds of the grapes usually provide more than enough tannin.

Stems also have certain flavours that winemakers only want in particular types of wine. You may have come across a term called “whole-bunch fermentation”, which, as the name suggests, is when whole bunches (including the stems) are fermented as is.

This gives the wine a completely different flavour and aroma profile. “Herbaceous” is a word often used. The risk is though, that it can lead to overly astringent tannins and “greenness” in the wine.

Loving our blog? Sign up for weekly updates straight to your inbox…

[withwine type=’join-mailing-list’]

Pressing

Crushing grapes and letting gravity do the rest of the work isn’t the most economical use of your harvest.

That’s where pressing comes in. After all, more juice equals more wine!

Pressing (or pressurage in French) “is an operation whereby pressure is applied, using a press, to grapes, grape clusters, or grape pomace in order to squeeze the liquid out of the solid parts”(thanks again Jancis!).

Historically pressing grapes was done by hand or by foot. This is not a very sanitary way to go about making wine!

Today most wineries use a mechanical press of some sort. These come in two basic varieties…

A batch press can handle up to 1-5 tonnes per hour. This type of press is used by small to medium-sized wineries. Grapes are loaded in one “batch” at a time.

Continuous presses on the other hand are fed a continuous stream of grapes. A continuous press can process up to 100 tonnes per hour. As you might have guessed a continuous press is geared more for a factory winery pressing thousands of tonnes of grapes at harvest.

For now, let’s concentrate on batch presses…

Types of Batch Presses

1. Basket Press

In recent history, the first mechanical press was the basket press. This iconic piece of machinery is still a reliable way to go these days (particularly for small batches).

A basket press has a ring of vertical staves (just like a barrel) with gaps between them (not like a barrel!). Grapes are loaded into the top. Then a wooden plate is lowered down over the grapes. A ratchet is used to slowly apply downward pressure to the grapes. This squeezes them tight against the staves (and each other) and pushes the juices out.

Here is a picture of one. It’s missing one-half of the staves so you can see the grape “marc” (skins and seeds) left behind after the grapes have been pressed.

If you can’t get your head around how it works (I obviously didn’t do a very good job of describing it!), then here is a quick video.

Bladder Presses

Also known as pneumatic presses these are quite common in small to medium-sized wineries (like Lodestone where Rob makes his wine!). These presses have either vertical staves as on the basket press or a cylindrical piece of sheet metal with holes in it for the pressed juice to flow through.

The difference is the pressing mechanism. In the middle of the press is a rubber bladder that is filled with either water or air. As it expands from the center of the press the grape skins are pushed up against the outer ring.

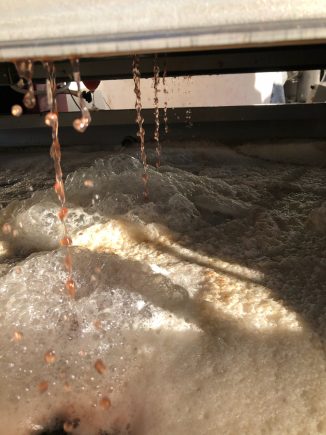

Here is a photo of some lovely Pinot juice coming out of the bottom of the press at Lodestone…

And, again… if you’re struggling to get your head around how a pneumatic press works, then check out this video where some bloke named Charles explains it all (thank you YouTube!)!

Things to Consider when Pressing

1. How much pressure should you apply?

This wasn’t an issue when grapes were stomped. However, with mechanical presses, we have the ability to apply so much pressure that we can rupture the seeds and introduce some harsh tannins and green plant tastes to the wine.

Apply too much pressure and you’ll have funky wine. Apply too little pressure and you’ll be leaving juice behind. This is where experience comes into play.

2. How much press juice versus free run juice do you want?

As we’ve talked about already pressed juice will taste different from free run juice. A winemaker might combine 90% free run juice with 10% pressed juice. This ratio the bulk of your wine is made from premium materials. The 10% pressed juice adds color, tannins, and complexity to the wine.

Some wineries go as far as producing two different “grades” of wine. The free run juice goes into the top shelf wine while the pressed juice is made into a “table” wine.

This is part of the artistry of winemaking. Despite all the science, there’s still a lot of art to this process!