I love it when our readers come up with ideas for blog topics. And no… not just because then I don’t have to!

One of our long-term followers came to me with this brilliant suggestion a couple of weeks back.

Thanks, Froggy!

Now… I don’t want to start any arguments here, but there is evidence to suggest the planet is getting warmer.

And whether we agree with it or not, the rise in temperature is already having a significant impact on agriculture.

And if you’ve been paying any sort of attention at all you’ll understand that wine is first and foremost an agricultural product. The grapes used to make it are grown and harvested to be fermented into wine.

This means that wine production is vulnerable to the effects of climate change (or whatever you want to call it!) from the health of vines to the taste and quality of the finished product.

And the thing is, wine grapes are extremely sensitive to climate. Winemakers rely on this fact to make different styles of wine. But it also means wine grapes are extremely sensitive to any changes in climatic conditions.

Around the grape-growing and wine-making world, smart producers have contemplated and experimented with adaptations. And not only to hotter summers, but also to warmer winters, droughts, hailstorms, frosts, flooding and bush fires. Shall I go on??!

Grape growers have been noting profound changes in weather patterns since the 1990s.

And more disruptions are coming. Much faster than anybody expected.

The accelerating effects of climate change are forcing the wine industry to take decisive steps to counter or adapt to the shifts.

So far, these efforts are focused on five factors…

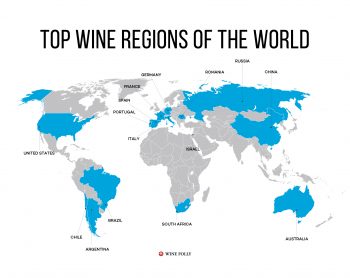

1. Expanding wine map

Winemakers are growing grapes in places once considered too cold for fine wines.

Winemakers are growing grapes in places once considered too cold for fine wines.

England is a perfect example. Thirty years ago, nobody had ever heard of English sparkling wine. But as the climate has warmed, a world-class sparkling wine industry has developed. New vineyards are being planted at a dizzying pace (primarily along the southern coast).

From Kent in the east through East and West Sussex, Hampshire, Dorset and as far west as Cornwall, fine sparkling wines are being made. Like our Somerled Sparkling they are produced by the same method as Champagne, but with their own character.

Many of the best vineyards are planted in chalky white soils that are geologically identical to the most prized soils of the Champagne region of France. Those soils have been in England for eons. But until recently, the climate was too cold. Now, Champagne companies like Taittinger have invested in English vineyards. No doubt hedging their bets as the climate in Champagne warms.

It’s not only England. Vineyards have been planted in places like Belgium, Denmark, Norway and Sweden!

In the Southern Hemisphere, growers are planting deep into Patagonia in Argentina and Chile. Some of these plantings are currently experimental, but these areas are bound to be more deeply explored in coming years.

In 2010, Brown Brothers purchased the Tamar Ridge and Gunns vineyards for this very reason. Together they make up about 50% of Tasmania’s vineyards. This was a deliberate strategic move to hedge their bets against warming climates.

2. Finding higher ground

Producers are now planting vineyards at altitudes once considered inhospitable to growing wine grapes.

Producers are now planting vineyards at altitudes once considered inhospitable to growing wine grapes.

No hard-and-fast rules limit the altitude at which grapes can be planted. It depends on a region’s climate, the quality of the light, access to water and the nature of the grapes. But clearly, as the earth has warmed, vineyards are moving higher.

At higher elevations, peak temperatures are not necessarily much cooler, but intense heat lasts for shorter periods. And night time temperatures are colder than at lower altitudes. This helps grapes to ripen at a more even pace, over a longer period of time.

But pushing altitudes also creates challenges. Soils, particularly on slopes, are generally poorer, water is scarcer and unexpected weather events like hailstorms are always a threat.

Loving our blog? Sign up for weekly updates straight to your inbox…

[withwine type=’join-mailing-list’]

3. Restricting Sunlight

For centuries, a formula governed the placement of some of the world’s greatest vineyards in the Northern Hemisphere. They would be planted on hillsides, with suitable soils, facing south or southeast, where they would receive the most sun and warmth, allowing grapes to fully ripen.

As areas in the Southern Hemisphere were planted with grapes, the reverse was true: North-facing slopes were most in demand.

As the climate has changed, however, the problem for wine producers is no longer how to ripen grapes fully but how to prevent overripening. This has caused many growers to reorient their thinking.

In the Yarra Valley, grower and winemaker Mac Forbes signed a lease in 2017 for about 10 acres facing south. There he planted chenin blanc, pinot noir and nebbiolo, all of which benefit from a relatively cool climate.

At vineyard level, that logic also affects how rows of vines are oriented. In new plantings, growers attempt to protect grapes from the afternoon sun, when the heat and light are at their most intense.

4. Experimenting with different varieties

For many producers, new vineyards in cooler environments are not an option. Instead, some are leaving behind the grapes that have long been associated with their region, and selecting ones more appropriate for the changing climate.

It may seem impossible to imagine Bordeaux without cabernet sauvignon and merlot, or Champagne without pinot noir and chardonnay, but the prospect of a much warmer future may require even the most famous wine regions to rethink their methods.

This is already happening experimentally in Bordeaux and Napa Valley, two prestigious regions closely associated with cabernet sauvignon.

In Bordeaux, where producers may use only grapes that are permitted by the appellation authorities, seen additional grape varieties have been selected for experiments to determine whether they can be used to mitigate the effects of climate change.

They include four red grapes…

- touriga nacional: a leading grape of port;

- marselan: a cross between cabernet sauvignon and grenache;

- castets: an almost forgotten variety that is resistant to certain diseases; and

- arinarnoa: a cross between cabernet and tannat. It’s a late-ripening variety which may protect against spring frosts.

The three whites include…

- albariño: the main white grape of northwestern Spain, which may be a good alternative to sauvignon blanc;

- petit manseng: from southwestern France, which can make both dry and sweet wines; and

- liliorila: a little-known cross between chardonnay and the obscure baroque that is highly aromatic.

The authorities will carefully monitor these grapes and consider their inclusion in the list of permitted varieties.

Some producers in Napa Valley are already experimenting with varieties other than cabernet. Varieties include familiar California varieties like zinfandel, petite sirah (durif) and charbono. They are also working with grapes from warm European regions, like touriga nacional, tempranillo from Spain and aglianico from southern Italy.

5. Understanding unpredictable weather

In agriculture, experience counts for an awful lot. No two years are identical, but growers will have seen many different weather events and learned how to respond over time. Meticulous historical records can be a huge help.

In agriculture, experience counts for an awful lot. No two years are identical, but growers will have seen many different weather events and learned how to respond over time. Meticulous historical records can be a huge help.

In the past, experienced farmers generally knew what to expect from the weather. The impact of climate change has made it much harder to predict.

It hails when it never used to hail, rains in the summer when it used to be dry, is dry in the winter when it used to rain.

Bush fires, floods, droughts — wine regions will have to learn how to deal regularly with these once-rare devastating events.

Here in Australia, we have led the way in researching how smoke from fires can taint grapes and wine. We’re also trying to figure out solutions that will at least make such wines drinkable.

The Côte de Beaune region of Burgundy has recently had several disastrous vintages due to hail. As such a system that tries to prevent the formation of hailstones by shooting particles of heated silver iodide at storm clouds has been installed. If that method fails, farmers may also put up hail netting in an effort to protect their vines.

Viticulture by its nature is complicated.

As the world’s climates are transformed, it is only becoming more so.

Somerled Club Room

For those of you who have heard rumours about our “New Club Room”…

The renovations have started!!

I do have some sad news though. The spa had to go…

I know we could have had some interesting events if we’d kept it. Unfortunately, it had to make room for our new bathroom and butler’s pantry.

Stay tuned for the after photos along with more progress updates.

We can’t wait to share the finished product with you!